If I told you that I studied circadian rhythms, it probably wouldn’t mean very much to you. What about ‘chronobiology’? The biology part is easy enough, the study of living things, but what about ‘chrono’? These scientific names obscure a simple fact about being human that most of us take for granted – that our daily lives are governed by time. We are awake in the day and asleep at night. We eat when the sun is up (generally) and fast in the dark (more or less). Chronobiologists (from the Greek ‘Chronos’, the God of Time) study these daily rhythms which they refer to as ‘circadian’ (from the Latin meaning approximately 24 hours).

This is all well and good, but you probably didn’t need scientists in a laboratory to tell you that you sleep at night and are awake in the day. So why should anyone care about chronobiology? Well, because time and its rhythms, once so important to our physical, emotional and spiritual lives, has been slowly dropped out of our daily experience over the last 120 years. Plus, understanding better how our bodies tell time and keep time could hold the key to a better, healthier life. When you sleep, when you eat, when you take your medicines, when you exercise – we evolved so that each of these fundamental activities correlates to a specific ‘when’. But in our modern society where we can have whatever we want, basically whenever we want, our earlier understand of time has gone right out the window. And that is a problem for our bodies which evolved to live a very different kind of life. It is making us sick.

Circadian rhythms are a huge topic which you could take so many different directions. This is a challenge and an opportunity for me as I’ve recently joined the Medical Museion as a postdoctoral researcher to work on exactly this – what does the science of circadian rhythms mean to us? What do these discoveries mean about how we work, how we engage with the environment and with each other? What can circadian disruption tell us about how we are living our lives and what we value in our modern world? How have people thought about time and its relationship to health in the past? How have our natural rhythms inspired artists and writers? These are questions I hope to unravel over the next few years.

Our daily rhythms evolved, like all other living creatures on the planet, from the Sun. The Earth spins around the sun in what is (approximately, depending on where you live) 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. Scientists think that the earliest circadian rhythms developed so that single celled organisms would seek shelter from damaging UV rays while they underwent the hazardous process of division. Our bodies still do a lot of complex work while we are sleeping. You could argue that the 24-hour measure is a construct (which is certainly is) but regardless of the human invention of clock time, our bodies do more or less the same thing over standard periods equivalent to one earth rotation, however you describe it.

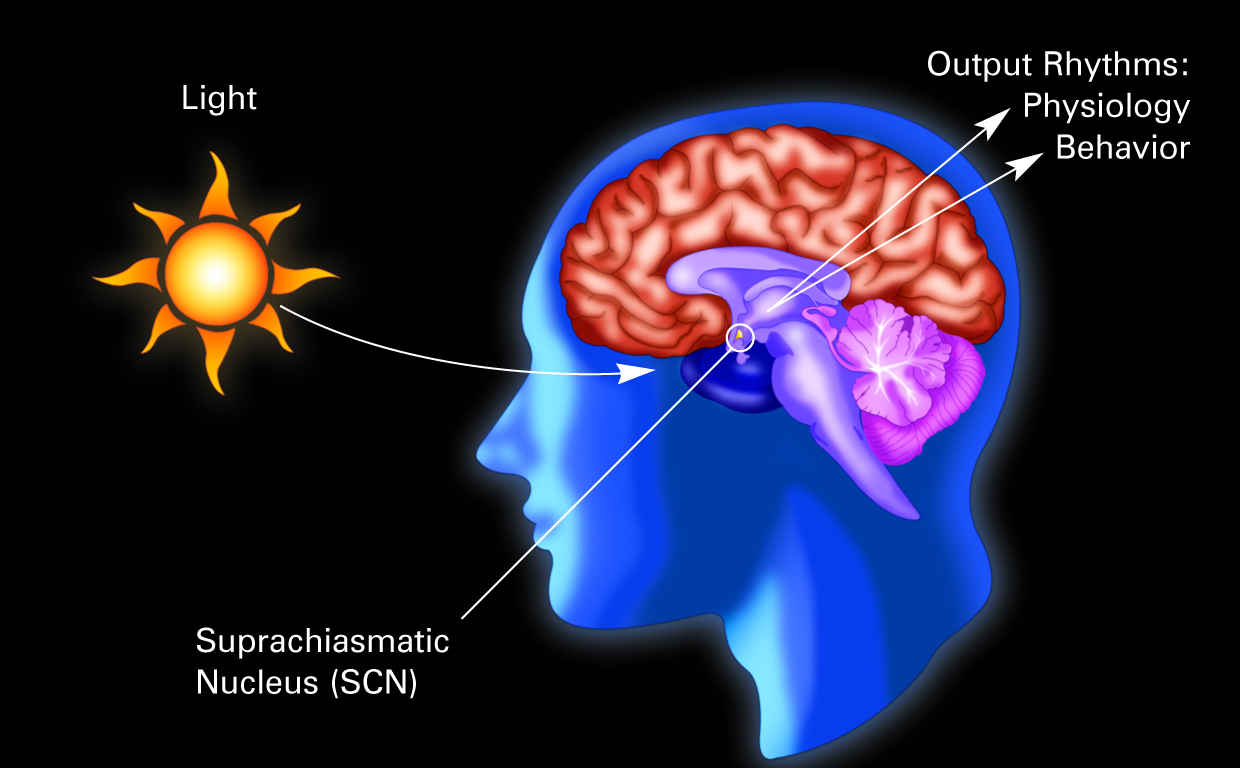

Any human alive for as long as we have been humans could have told you as much. But how do our bodies know what time it is? What exactly is happening inside of us? And why exactly do we do this? These are questions which fascinate chronobiologists today and many scientists throughout history, including Charles Darwin. Since the 1960s, we’ve gotten a lot closer to answering some of these questions. For example, we now know that our brains have a central hub, just between our eyes called the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (SCN) which acts as a master clock, keeping our internal processes in time with the outer world. And that clock is reset every day via specialized photoreceptors in our eyes which sense daylight and make a special pigment called melanopsin. We also know the different parts of our body have their own clocks (like the liver) and that they even respond to environmental cues beyond just the sun, like what we eat.

Knowing more about how the body should be working can help us to also understand what might be going on when things aren’t working so well. In particular, pressing health concerns like rising obesity levels, diabetes and other metabolic syndromes, and even heart disease, are being linked to body clocks which aren’t synched up quite right. For example, we know nurses working the night shift are much more likely to develop breast cancer. So much so, that in 2007 the International Agency for Cancer research declared that shift working was ‘probably carcinogenic’ to humans. In 2009, Denmark made headlines for agreeing to pay compensation to women who had developed cancer as a result of shift-working. Our body clocks work hard to keep us in tune with our environment – but when we push it too far, it can have incredibly dangerous results.

As we learn more about our body’s rhythms and their complex entanglement with the environment, it poses important questions about ourselves. Can we continue to support a 24/7 economy when we know it is risking our lives? If we rely on our natural world to ‘tune’ our clocks, what obligations do we have to nature? If circadian disruption is a symptom of ‘modernity’ – when does being ‘modern’ start (and end?) And isn’t time just a construct anyway?

For now though I will leave you with the words of American philosopher and statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790):

Dost thou love life? Then do not squander time, for that’s the stuff life is made of.