Asbestos causes lung cancer. Smoking is responsible to the majority of lung cancers. A specific genotype increases your risk of breast cancer, and measles is a virus that if not prevented can cause brain damage or in sever cases death.

All the above statements are scientifically supported facts, identified through public health research. Unfortunately, the world of Public Health Sciences is not all facts. Lots and lots of possible connections, probably associations and complex causal structures determines our wellbeing, health and life span. Read any peer-reviewed health journal and many of the articles will have titles such as ‘indication of…’, ‘probable…’, ‘likely association…’ and the conclusions will be full of reservations and expression of the need for further research. In many ways it illustrates the premises of science – that answering one questions gives rise to a whole bunch of new ones.

All the above statements are scientifically supported facts, identified through public health research. Unfortunately, the world of Public Health Sciences is not all facts. Lots and lots of possible connections, probably associations and complex causal structures determines our wellbeing, health and life span. Read any peer-reviewed health journal and many of the articles will have titles such as ‘indication of…’, ‘probable…’, ‘likely association…’ and the conclusions will be full of reservations and expression of the need for further research. In many ways it illustrates the premises of science – that answering one questions gives rise to a whole bunch of new ones.

The complexity and uncertainty in much health research is one of the reasons that headlines on news papers may change between “Chocolate can kill you”, “Or this is how chocolates saves your life”. In addition, public health is not ‘owned’ only by scientific researchers. Public health is exactly public health and the public may contribute to the picture with their own experiences, such as “Soya milk cured my child from chronic ear infections” or “my child became autistic shortly after it had its first measles immunization.” All of which may contribute to confusion on what is true and what is false.

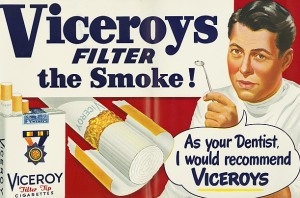

Research studies are only very rarely 100% conclusive and it is therefore practically impossible for researchers to make clear-cut statements about health risks of various exposures. And this can be used to the advantage of industries or people for whom doubt is enough to sell a product or an idea. This is very well illustrated in this small video called “Doubt” made by The Climate Reality Project. The video shows how scientists inability to draw unambiguous conclusions can be turned to the advantage of for example tobacco companies and climate change sceptics. Add to that a lot of propaganda and the scientific community are up against a tremendous challenge, illustrated by this short quote from the film:

“They [the tobacco companies] realised that the science doesn’t need to be disproven – it was enough to create doubt in the minds of the public to keep them from recognising the truth”.

The video, which takes the case of smoking as an example of how disagreement among scientists or their inability to make non-debatable conclusions (at least in the early stages of research), illustrates that public scepticism towards and doubt in what scientists argue has existed and flourished long before social media came into existence. In this case it is the damaging effects of smoking, but acid rain or nuclear risks are other examples.

Today, social media surely plays an important role in the scepticism towards eg. vaccines and climate change. And it enables it to spread quickly. What is the solution to that? That we close our eyes and say that social media is dangerous because it spreads non-scientific ideas? That seems a bit naive. Social media is unlikely to disappear, and so are all the blog posts, Twitter discussions and Facebook postings warning against measles vaccines etc. From my perspective the solution is for scientists, research institutions and other representing the scientific community ALSO to get out there, and make their view, knowledge and opinion head.  Just like social media is a platform to quickly spread incorrect knowledge it is equally good for spreading correct (in the eyes of science) knowledge and not let the allegations go unanswered. Of course social media would or could never stand alone, but it is an important communication channel not to overlook or rule out because of fear. If fear of misunderstandings of researchers blogging or tweeting or doubt in the credibility of social media rules the science community’s use of social media then the researchers are no better than the public who responds to doubt and fear…

Just like social media is a platform to quickly spread incorrect knowledge it is equally good for spreading correct (in the eyes of science) knowledge and not let the allegations go unanswered. Of course social media would or could never stand alone, but it is an important communication channel not to overlook or rule out because of fear. If fear of misunderstandings of researchers blogging or tweeting or doubt in the credibility of social media rules the science community’s use of social media then the researchers are no better than the public who responds to doubt and fear…

public health science communication

Communicating the doubtfulness of Public Health Sciences

Asbestos causes lung cancer. Smoking is responsible to the majority of lung cancers. A specific genotype increases your risk of breast cancer, and measles is a virus that if not prevented can cause brain damage or in sever cases death. All the above statements are scientifically supported facts, identified through public health research. Unfortunately, the […]